Remarks I shared at the first faculty assembly of the 2023-24 school year at West Virginia Wesleyan College:

This time last year many of us were understandably stressed about the potential of ChatGPT and later Chat GPT4 to destroy higher education as we know it—not to put too fine a point on the heights our anxieties could reach. A year later, we’ve probably all got stories to share and wisdom to offer about how we managed this chilling new thing in our discipline-specific ways. And we are likely still trying to figure out best practices for the coming year and beyond. Certainly, colleges and universities everywhere are scrambling to have the smart, winning position on this, whatever that might be.

What I’d like to do in my brief time here is note a couple of things that the emergence of this new technology reveals about the very old practice of teaching the young. I’m not talking about artificial intelligence in the broad sense—that catch-all term for cognition-like capabilities that will either save us or end us, depending on your point of view. Rather, I mean these text-based conversational AI agents like chatbots and what we are to make of them pedagogically, other than the enemy.

First, I wonder if we’ve paid sufficient attention to the ways these platforms can actually enhance learning, especially for students who come to us with gaps in the knowledge and skills we expect of them. Note to self here and maybe to you, too: we should cherish the students we get, not pine for the students we wish we had.

ChatGPT can be used effectively as a tutoring tool, generating things like individualized practice problems and questions, along with instant feedback. It offers personalized study advice for students who struggle to work smarter, not just harder. ChatGPT can improve accessibility to content for students with disabilities, like audio and visual aids, and provide them support services that aren’t always available in person or easy to get to.

Second, how much of our angst around chatbots is because we secretly, or not so secretly, suspect that our students are just itching to pull one over on us? Another note to self here and maybe to you, too: let’s not communicate to students, overtly or even in subtle ways, that we expect they will cheat. That is a form of cynical defeatism I am prone to myself, but it’s neither fair or wise. I don’t believe that most young people come to college hoping to game the system or dupe their professors or scam their way to their degree. I think most of our students are dealing with responsibilities and heartaches and trauma we have no idea about, and that the pressures they feel to “succeed”—from family, friends, coaches, and our competition-driven culture—send some of them down a spiral of bad decisions that can lead to disastrous consequences. And some of those disastrous consequences are put in place by us because we’re persuaded that cheating is a student’s default mode (or the default mode of certain students) and we feel furious and helpless to do anything about it.

Maybe our anxiety and fury about ChatGPT could be channeled into energy better spent in taking more seriously a collaborative model of education. Paolo Friere, the Brazilian philosopher, educator, and political activist, in his book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, criticized what he called the “banking” concept of education: the idea that teaching is an act of depositing information into the repositories that are passive, individual students. We know that this is not only an ineffectual way to teach but a dehumanizing one as well since, as Friere observed, all real learning is social and collaborative in nature: “The teacher and the taught together create the teaching,” he famously said. This is a model of teaching and learning that encourages active in-class inquiry, curiosity-led participation, and critical literacy—the skill set one needs in any discipline, and for any future vocation, to think critically about what one is reading, hearing, seeing, and to develop a critical consciousness that has the language and the ability to assess: is this fair? is is just?

This collaborative pedagogy can open our imaginations to ways of assessing student learning that don’t rely so much on the kinds of assignments that ChatGPT excels at. And even if you’re not persuaded by the collaboration model of teaching and learning, it is on us to design assignments that can’t be performed readily and convincingly by a chatbot.

And what are some ways that ChatGPT might help us with tasks we don’t love doing, like some forms of grading, generating quizzes, crafting practice questions for tests, and so on. Who among us doesn’t want more time for the lifegiving aspects of our vocation and more time for having a life?

Let me be clear: I am for embodiment. For presence. For human connection. In teaching and in life. And I have deep concerns about these generative AI platforms. I worry about the very loss of embodiment, presence, and human connection they represent. I worry about bias and inaccuracy. I worry about the over-dependence, the addictions, even, they can induce.

But the question is not: is ChatGPT good or bad? The question—which is the question for any technology, really—is: what sort of person will the use of this technology make of me? And: what habits will the use of this technology instill? And: how will it affect how I relate to other human beings? And: what practices will the use of this technology replace? And: what will the use of this technology encourage me to notice? Cause me to ignore? And: what was required of other human beings, of other creatures, of the earth, so that I might be able to use this technology?[1]

So we should do all we can to discourage students from asking a chatbot to compose their written assignments. Run those AI content detectors if you must. But this moment presents bigger challenges than that to us and to our students. It poses worthy questions that have been around longer than AI and ChatGPT but are newly urgent. I hope we are interested in exploring them with depth and nuance, both personally and collectively. I’d welcome such conversations.

Cheers to a new school year, everyone.

Thank you!

[1] These questions are from Michael Sacasas’ essay “The Questions Concerning Technology” on his Substack “The Convivial Society.” He also talks about the essay on an episode of the podcast “The Ezra Klein Show.”

and the body. But the news of the test helped explain his rapid decline in the week or so before he died. My mother, my husband, and I had been with him in his last hours. We have tested negative for the virus and have developed no symptoms. Our current self-isolation isn’t much different from the sheltering-in-place we’ve been doing since mid-March.

and the body. But the news of the test helped explain his rapid decline in the week or so before he died. My mother, my husband, and I had been with him in his last hours. We have tested negative for the virus and have developed no symptoms. Our current self-isolation isn’t much different from the sheltering-in-place we’ve been doing since mid-March. the narrative unfolds through the journal entries of Lauren Olamina, an African-American teen who navigates life in a dystopian America in the mid-2020s. Social, economic, and environmental collapse force Lauren and everyone else to survive however they can in a frightening, dangerous world.

the narrative unfolds through the journal entries of Lauren Olamina, an African-American teen who navigates life in a dystopian America in the mid-2020s. Social, economic, and environmental collapse force Lauren and everyone else to survive however they can in a frightening, dangerous world.

truthfully, to wield language responsibly) and the loss of the world (its destruction by forces of hatred and self-interest and our culture’s willing and often unwitting collusion with them).

truthfully, to wield language responsibly) and the loss of the world (its destruction by forces of hatred and self-interest and our culture’s willing and often unwitting collusion with them). figures, the widespread employment of racial and ethnic fears and grievances, attacks on governmental, judicial, journalistic and scientific institutions, and the increasing vulnerability of migrants, refugees and all displaced people.”

figures, the widespread employment of racial and ethnic fears and grievances, attacks on governmental, judicial, journalistic and scientific institutions, and the increasing vulnerability of migrants, refugees and all displaced people.” sufficiently serious but not heavy-handed, memorable but not (too) controversial. And the fear of being boring–that you’ll look out over the sea of faces and, oh my god, are they texting while I’m talking? 22-year-olds can be a tough audience; I don’t envy those who stand in front of them every graduation season and do their best to challenge and inspire.

sufficiently serious but not heavy-handed, memorable but not (too) controversial. And the fear of being boring–that you’ll look out over the sea of faces and, oh my god, are they texting while I’m talking? 22-year-olds can be a tough audience; I don’t envy those who stand in front of them every graduation season and do their best to challenge and inspire. Seven Last Sayings

Seven Last Sayings has come to feel obligatory in this age of death-notice-via-social media. I’m not a fan of the latter. But I do want to communicate my affection for my philosopher friend.

has come to feel obligatory in this age of death-notice-via-social media. I’m not a fan of the latter. But I do want to communicate my affection for my philosopher friend. was a little vexed).

was a little vexed). visuals, in symbols and associations with the familiar story of a displaced couple in dire straits: an illegitimate pregnancy, harassment from political authorities, shunning and rejection from local businesses, an uncertain future.

visuals, in symbols and associations with the familiar story of a displaced couple in dire straits: an illegitimate pregnancy, harassment from political authorities, shunning and rejection from local businesses, an uncertain future.

woman does stride–with $5000 in cash and a sorrow that has crushed her.

woman does stride–with $5000 in cash and a sorrow that has crushed her. intent is hardly disguised: “human interest” stories like these are meant to restore our faith in the basic decency of humans. And to boost advertising revenues for the network.

intent is hardly disguised: “human interest” stories like these are meant to restore our faith in the basic decency of humans. And to boost advertising revenues for the network. Drew who, at the time, was an avid Duke basketball fan. That Drew would go on to become a Blue Devil-hating UNC Tarheel didn’t diminish one speck of affection for the name of our “Dukie.”

Drew who, at the time, was an avid Duke basketball fan. That Drew would go on to become a Blue Devil-hating UNC Tarheel didn’t diminish one speck of affection for the name of our “Dukie.” will lie here under green grass and white snow, season after season and, while I don’t envision a reunion with Duke in some meadowy heaven, I have the hope that the goodness that was his very being participates somehow in what Dante called “the love that moves the sun and the other stars.” And if I can live with the kind of integrity and fullness of life that was our Duke, and if I can die with the same grace and gratitude, I will have been made more fully human, in no small part, because of this beautiful animal.

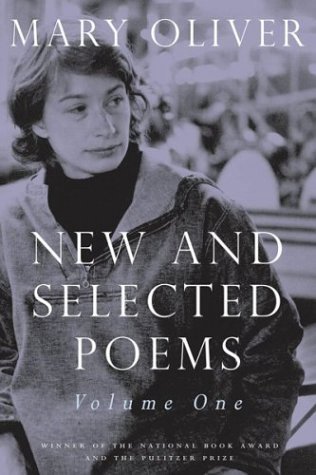

will lie here under green grass and white snow, season after season and, while I don’t envision a reunion with Duke in some meadowy heaven, I have the hope that the goodness that was his very being participates somehow in what Dante called “the love that moves the sun and the other stars.” And if I can live with the kind of integrity and fullness of life that was our Duke, and if I can die with the same grace and gratitude, I will have been made more fully human, in no small part, because of this beautiful animal. reveal the theological and liturgical edges of Oliver’s work during this period of her life.

reveal the theological and liturgical edges of Oliver’s work during this period of her life. story is his struggle to know and name his body’s desires. In fact, that way of putting it—that Moonlight is a movie about sexual self-discovery—minimizes, I think, both the beautiful sweep of this particular story set in this particular place among these particular people and what it means to know ourselves as desiring beings.

story is his struggle to know and name his body’s desires. In fact, that way of putting it—that Moonlight is a movie about sexual self-discovery—minimizes, I think, both the beautiful sweep of this particular story set in this particular place among these particular people and what it means to know ourselves as desiring beings.

especially for people who care deeply about language and its power to compel, convince, convert.

especially for people who care deeply about language and its power to compel, convince, convert. of her work; accessibility in poetry seems to disincline serious scholarly engagement. It is true that her substantial output is mixed, a hazard for anyone in any field whose published work spans more than half a century. It’s also true, I think, that her best poems are not her most popular poems.

of her work; accessibility in poetry seems to disincline serious scholarly engagement. It is true that her substantial output is mixed, a hazard for anyone in any field whose published work spans more than half a century. It’s also true, I think, that her best poems are not her most popular poems. time and space and money to do this kind of work. It also has its challenges–how, for instance, to thrive in one’s aloneness rather than succumb to loneliness.

time and space and money to do this kind of work. It also has its challenges–how, for instance, to thrive in one’s aloneness rather than succumb to loneliness. in Philadelphia, the Democrats sought to counter the dread and despair with

in Philadelphia, the Democrats sought to counter the dread and despair with  fully participated. We are not innocent of making war against civilian populations. The modern doctrine of such warfare was set forth and enacted by General William Tecumseh Sherman, who held that a civilian population could be declared guilty and rightly subjected to military punishment. We have never repudiated that doctrine.”

fully participated. We are not innocent of making war against civilian populations. The modern doctrine of such warfare was set forth and enacted by General William Tecumseh Sherman, who held that a civilian population could be declared guilty and rightly subjected to military punishment. We have never repudiated that doctrine.” legitimate work for human beings to do. I note in our conversation that there might also be such a thing as

legitimate work for human beings to do. I note in our conversation that there might also be such a thing as

Academic sabbatical: a period in which one is to be demonstrably productive.

Academic sabbatical: a period in which one is to be demonstrably productive. This long-time friend had me at “it would be good.” But I suspect that for many Christians on both

This long-time friend had me at “it would be good.” But I suspect that for many Christians on both

In my brief, limited experience, meals in the city of Florence are occasions for conviviality more than caloric intake.

In my brief, limited experience, meals in the city of Florence are occasions for conviviality more than caloric intake.

of

of